Listening as Resistance: Jazz, Politics, and Artistic Responsibility

Listening as Resistance: Clayton Thomas on Jazz, Politics, and Artistic Responsibility

Jazz is more than music. It is protest, innovation, and survival. For double bassist Clayton Thomas, it is also a responsibility—a refusal to be silent in the face of injustice.

Through deep listening, radical improvisation, and fearless advocacy, Thomas disrupts the passive consumption of art and demands engagement. In a time when silence is complicity, he asks us: Are you really listening?

By Michelle St Anne

When we talk about jazz, we often discuss it as a style, a genre, a sound. But for double bassist Clayton Thomas, jazz is not just a form of music—it is a force, a historical and social trust, a commitment to innovation and integrity.

"Jazz is a music of innovation and social integrity," Thomas explains. "It is deeply non-capitalistic at its core—a cultural survival music. I trust the jazz community historically as aesthetic guides in how to deal with time and history."

This perspective was not the answer I was expecting, but it struck a chord. So often, we think of jazz in terms of its technical elements—its improvisations, its syncopations, its chord structures. But Thomas brings us back to its origins: a political movement, a response to oppression, a call to action.

Of course, this doesn’t mean he disregards the style. "Half my record collection is traditional jazz," he says. "But jazz extends into multiple other communities. Except, of course, when it becomes a nostalgic money grab and loses its innovation. But that's capitalism."

Sounding the Alarm: Music as Political Action

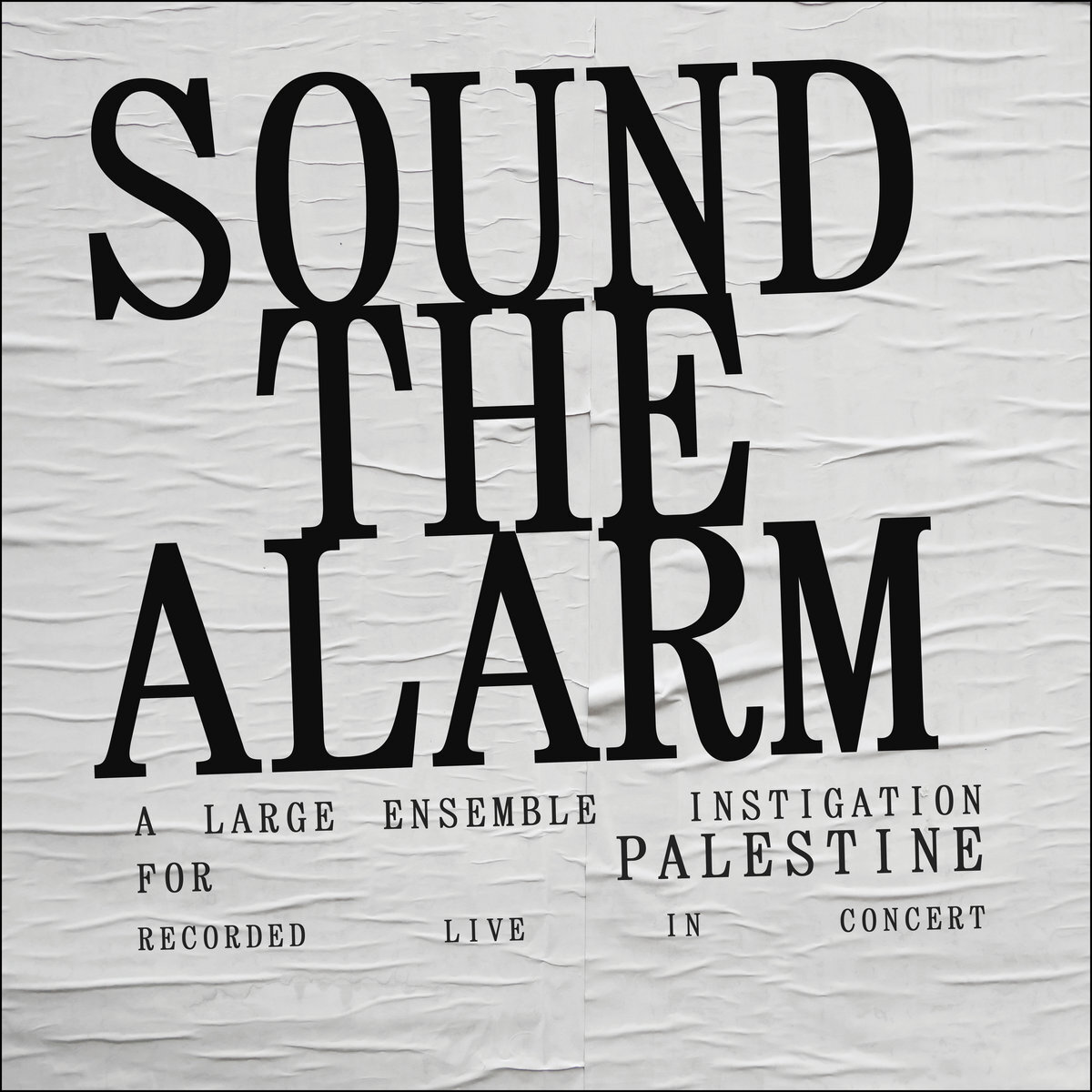

Thomas is no stranger to using his music as a form of protest. In 2023, he formed Sound the Alarm, a 17- to 20-piece improvising ensemble, to raise funds for humanitarian efforts in Gaza.

"There was an endemic silence from the improvised and experimental music scene in Sydney," he says. "Not that social atrocity is new, but the scale of what we were witnessing made it impossible for me to look away. So I put together this band to say: This is happening. And we cannot be silent."

The project also redefined how he structured his compositions. Unlike his usual approach to improvisation—where large groups of musicians are guided by subtle cues and intuition—this was more deliberate. "I wanted the audience to have a distinct experience," he explains. "One piece focused on image, another on social behaviour. When you came to this concert, you knew what you were coming for."

Performing in Germany, he encountered another layer of complexity. Wearing a keffiyeh draped over his bass, he gave a short speech about Palestine before each performance.

"Germany is having a difficult time knowing how to talk about Gaza and antisemitism. And they are violently cracking down on community groups advocating for an end to the violence. But I made it clear: If you are here to listen to my music, you need to know what is on my mind. Because improvised music is about tapping into the universe at any given moment. And if I can’t turn away, then neither can you."

Improvisation as a Practice of Listening

Improvisation—at least in the way Thomas engages with it—is not about chaos. It is about deep listening. About entering a space with an awareness of the people, the instruments, and the energy around you. "The simplest thing I remind myself before playing is: Listen," he says. "Make sure you are here to listen."

He likens it to painting: "Make sure you can see what you are doing—not just act. Give yourself room to see. To perceive."

But preparation is key. "I have to be in shape, be practicing, be ready to follow what I hear. If I can’t, then I’ll only be thinking about failing, and that’s not inspiring."

Failure, though, is a complicated concept. "I hate failing," he admits. "That feeling of I fucked that up—it does not make me happy. But I also know that in the studio, in the space where you are experimenting, failure is essential."

The Role of Art in a Capitalist Culture

Towards the end of our conversation, we touch on the tension between artistic practice and creative practice—something that has been on my mind in discussions around advocacy for artists.

"What does creative practice mean to you?" he asks me, flipping the interview on its head. For me, it is the distinction between making work that is part of an artistic lineage and making work that serves a function—whether in advertising, branding, or entertainment. And this brings us back to the commodification of art.

Thomas, having once worked in advertising before shifting to charity fundraising, is quick to draw the line: "Advertising is the commercial commodification of the brain. Communication is not."

His work, both as a musician and an activist, seeks to resist that commodification. Whether through jazz, improvisation, or politically charged performances, Thomas challenges us to listen—to history, to the present, and to each other.

And in a world where silence is complicity, that listening is a radical act.

Clayton Thomas is a Double bass player and founder of the NOW now, Splinter and Splitter Orchestra.

Michelle St Anne is the Chair of the Inner West Creative Network and is the Artistic Director of The Living Room Theatre

Photo: Clayton Thomas in BELIEVE

RELATED CONTENT

READ: in conversation with Clayton Thomas

LISTEN: Thomas on Bandcamp

SUPPORT: Sound the Alarm