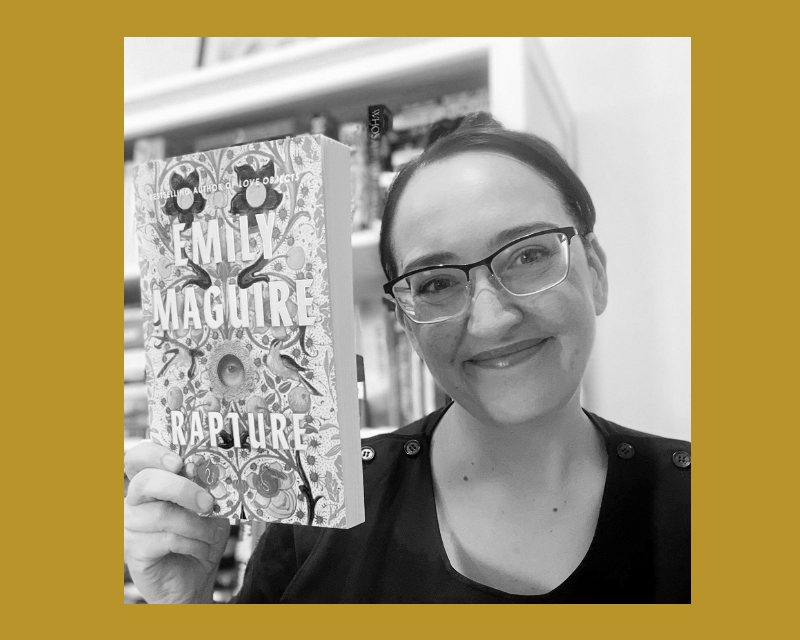

Creative Profile: Emily Maguire:

Emily Maguire is an Australian novelist and journalist who grew up in Western Sydney. She became a professional writer in her mid-twenties and is now the author of seven novels and three non-fiction books. Her novels have been translated into 12 languages and her articles and essays on sex, religion and culture have been published widely in newspapers and journals. She has an MA in literature and works as a mentor to young and emerging writers.

In 2013, Maguire was named as one of The Sydney Morning Herald Best Young Australian Novelists and she has since been listed for several awards including the Stella Prize, the Miles Franklin Literary Award, the Dylan Thomas Prize and the ABIA Literary Fiction Book of the Year.

Before addressing a topic you seem to undertake a great deal of research. Do you think fiction writers have to be true to the facts?

Facts are less important to me than creating a fictional world into which readers can stay immersed. So research for me is, in the first instance, about finding all the details to help create that world. Its secondary purpose is to make sure that there’s nothing so implausible that readers will be jolted out of the story.

What questions did growing up in a religious Christian environment leave you with? Is your latest novel ‘Rapture’ a way of dealing with some of these questions?

One of the big questions I’ve had over the last decade or so is why I continue to feel connected to the Christianity of my childhood even though I long ago rejected the institutional church and its teachings. Part of grappling with this big question involved reading a lot about the history of the church and this was how I first came across the medieval legend of a female pope. It’s an immediately appealing and fun story — she’s a trickster and adventurer, someone who chases an ever bigger life while completely hoodwinking her supposed superiors — but it’s also about all the things I’ve been thinking and writing about for twenty years: sex, patriarchy, shame and yes, definitely, faith and religion.

What has been the most challenging issue you have explored in your fiction writing?

Shame is very challenging to write about, because reproducing its effects can feel like perpetuating the shame itself which is the opposite of what I seek to do. It’s a continued challenge to write about the causes and manifestations of shame without inadvertently creating more of it in the world.

Is there subject matter you think you have to leave until you are older?

Not at all. I’ve always written about whatever I feel compelled to write about and hope I always will. I do think experience — as a writer, but also just as a human — changes the way any writer will approach or tackle their material, but not necessarily the subject matter or themes themselves.

In an interview, you once described yourself as an ‘extreme introvert’ and yet you choose to expose yourself through your writing. How does that compute?

Introversion is more about needing lots of alone time than it is about being shy or withholding. In any case, I don’t agree that I expose myself through my writing. The work I publish is carefully and artfully constructed to create certain effects while exposing only what I choose to. My writing is from me but it’s not actually me.

You have undertaken several residencies including at the Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney and at the Australian National University. What new avenues of thought do residencies like these liberate you to travel along?

Residencies offer an opportunity to step back from the familiar and explore new intellectual terrains. At both the Charles Perkins Centre and the Australian National University, I was surrounded by people whose work challenged and inspired me, and I was able to immerse myself in ideas that I might not have encountered otherwise. This cross-pollination of thought—whether it’s in the form of academic discussion, creative collaboration, or simply having time to read and reflect—helped me stretch the boundaries of my own thinking and writing.

You have enjoyed great success in getting your work published. Where would you position yourself in the Australian writing environment?

I think it’s always difficult to position oneself within any community, especially one as vibrant and diverse as the Australian writing environment. I’ve always aimed to just write the best version of the idea in my head that I possibly can and hope that it finds a publisher and then readers. I’ve been doing this for 20 years and in that time I’ve built great working relationships and also deep friendships with others in the industry, and these relationships definitely sustain me creatively and emotionally. To think about my position in relation to the people I work alongside, hang out with and love would feel weird. I’m just doing my thing and, when I’m lucky, connecting with others doing theirs.

When mentoring younger writers, what advice do you give them about the writing life ?

Generalised advice is hard, because every single writer comes with their own set of challenges and questions. Something I do always like to emphasise with new writers, though, is how important it is to give your work time to breathe and find its own shape. First drafts are for figuring out what the thing is, and every draft after that is about making it more itself. Some people think this means you need a lot of patience to write, but for me the patience comes more at the other end when submitting and publishing. Writing takes time but it’s an active process, you’re not just waiting around. I rarely think about how long a book is taking, because I’m so absorbed, and often entranced, by the work of writing it.

Article by Tamara Winikoff

Tamara Winikoff is an independent consultant with extensive experience in arts advocacy, policy, and cultural leadership. She was a a founding member of the Inner West Creative Network and served as Executive Director of the National Association for the Visual Arts (NAVA) for 22 years, championing artists’ rights and sector development. As Co-convenor of ArtsPeak, she coordinated national arts policy initiatives. Previously, she managed the Community, Environment, Art and Design (CEAD) program at the Australia Council for the Arts and lectured in Cultural Environment and Heritage at Macquarie University. Based in Sydney, she continues to influence the cultural landscape through strategic consultancy.